From the Whitney Museum to Tate Modern, workers at art and cultural institutions are discovering that unions aren’t just for hard-hats

In the late 1960s, as American society convulsed with radical energy, new protest groups cropped up at unprecedented speed. One of these was the Art Workers’ Collective (AWC) in New York City, a loose organization that primarily aimed its critique at the Museum of Modern Art. The AWC accused MoMA of, among other offences, constraining artistic and political expression and laundering the reputations of capitalists who sat on its board – many of whom, like the Rockefellers, supported the Vietnam War.

The AWC envisioned a more egalitarian artworld. Leading artistic and cultural institutions like MoMA relied on the labour of hundreds of people, from artists to archivists to cloakroom attendants, and the group felt that they should all have a voice in institutional decision-making, including the ability to bargain over pay and working conditions. As well as empowering art workers, the AWC also sought to make art more available to the public. In one creative act of protest, artist Joseph Kosuth designed a lookalike MoMA membership card, emblazoned with the AWC logo, which purported to grant the cardholder free entry. Unfortunately the AWC, like many radical groups of the era, was not long for this world. Members voted to solidify their project by forming an art workers’ union in 1970, but its scope was ill-defined and the effort fizzled.

Regardless, the AWC’s vision of a more democratic museum made an enduring mark on the New York artworld. As the AWC quietly dissolved in 1971, a new organization simultaneously arose, this one with staying power: a union for the staff at MoMA called the Professional and Administrative Staff Association, or PASTA. In announcing the group’s formation, the New York Times observed that it was the first union of its kind in the United States.

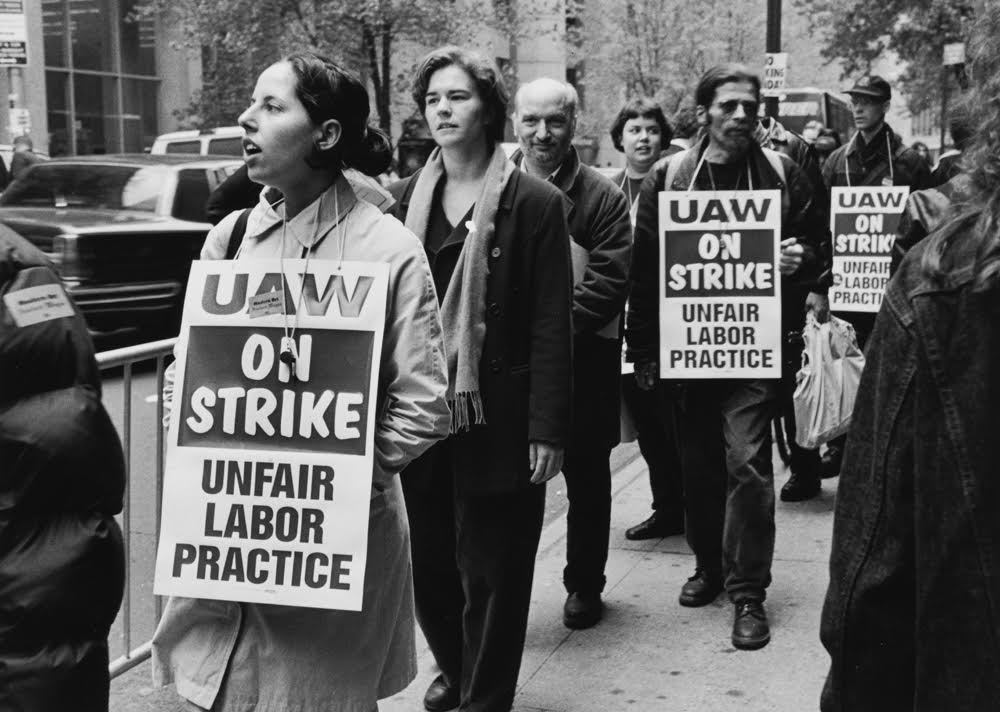

MoMA’s union still exists today as a chapter of the United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 2110, which represents several other art and cultural institutions in the US (including the New Museum of Contemporary Art and the New-York Historical Society). In the last few years UAW Local 2110 has experienced a massive swell of support, with workers at the Dia Foundation, MASS MoCA, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney all voting to join in the last year.

President of UAW Local 2110 Maida Rosenstein says that the old perspective on whether unions belong in cultural institutions – where jobs range from curators to security guards, but where professional staff sometimes have a hard time imagining themselves in a union – is rapidly changing. “In so many workplaces, whether it’s in publishing or in museums or universities, people had the idea that they were lucky to be in these prestigious institutions,” says Rosenstein. “It was a given that you should accept low salaries and poor treatment in exchange for being able to work at a place like the Museum of Modern Art or HarperCollins or Columbia University.” Now art and culture workers are increasingly internalizing the slogan PASTA used in the 1970s: ‘You can’t eat prestige.’

Across the Atlantic, Faiza Mahmood is an industrial relations officer at the UK’s Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers Union (RMT). But for nearly a decade before she elected to work full-time for the labour movement, she cut her teeth working and organizing at museums. While at the Museum of London, Mahmood served as secretary for her branch of the museum’s union, Prospect. There she encountered some of the thorny specificities of labour organizing in the cultural sector. “It’s a divided workforce. You’ve got people who work in back-of-house roles and front-of-house roles,” Mahmood says, referring respectively to professional jobs like donor relations and non-professional jobs like ticket sales.

Workers have the most power when they collaborate across this divide, whether they’re represented by the same or different unions. One of the first campaigns Mahmood participated in at the Museum of London, where she worked as an educational programmer, was over the front-of-house staff’s uniform shoes. “Their shoes were so uncomfortable that they couldn’t stand for eight hours wearing them. It was an issue they couldn’t raise until they got the back-of-house staff involved, who said, ‘Yeah, we’ll support you with this. We’re going to put it as part of our pay claim.’”

Gareth Spencer is a front-of-house duty manager at the Hayward Gallery of the Southbank Centre in London, and President of the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS) Culture Group, which is comprised of workers in the UK’s museums, galleries, and other cultural institutions. He says that the culture group has seen an influx of members since workers at Tate Modern went on a high-profile strike in 2020. “We’ve shown that unionized workplaces have better pay,” he says, encouraging workers at other museums and galleries to follow suit. As for how they might do it, “Get as many colleagues who are on the same page together as possible. Then pick a union.”

A Guide to Unionizing the Artworld

In most cases, forming a union at a single workplace actually consists of joining an established union that already represents multiple workplaces. When choosing a union to collectively join, workers should research institutions similar to their own, find out who represents them, and start placing phone calls to union offices to learn more and discuss the possibility of linking up.

After an existing union agrees to help organize a union drive, then begins the process of convincing coworkers of the utility of the union. A sizable group of workers announcing intent to unionize may convince an employer to voluntarily recognize the union. If not, workers can still win their union by either automatic statutory recognition or an election, depending on the national context; an election in which a majority vote ‘Yes’ is always required to win union recognition in the US, and is also required in the UK if worker support was not initially great enough to trigger automatic recognition. After workers have voted to unionize, they will begin to negotiate their first contract.

Mahmood stresses the importance of having a solid group of pro-union workers from the outset – people who are prepared to put in a lot of effort to win their union and first contract. “Before you’ve got a recognized union, there’s obviously the issue of trying to get time at work to do it. So it does take a bit of dedication, and a core of organized people who are willing to put in that work,” she says. She recommends using free WhatsApp groups to coordinate and holding regular meetings on lunch breaks and after hours. Once workers have assembled a core team and reached out to the right union, Mahmood also advises attending branch meetings to learn more and form relationships.

As for what not to do, Rosenstein warns against putting the cart before the horse. “Don’t start an Instagram account about how toxic your workplace is,” she says, and “don’t call a mass meeting of everybody to find out whether they want to form a union.” These hasty escalations can unnecessarily polarize workplaces and invite union-busting campaigns from management, catching fledgling union campaigns off guard. Instead, organizers should focus on having in-depth one-on-one conversations with coworkers to surface common grievances and identify strong supporters. Steady preparatory organizing will give the core team the tools they need to systematically and effectively convince coworkers who are on the fence.

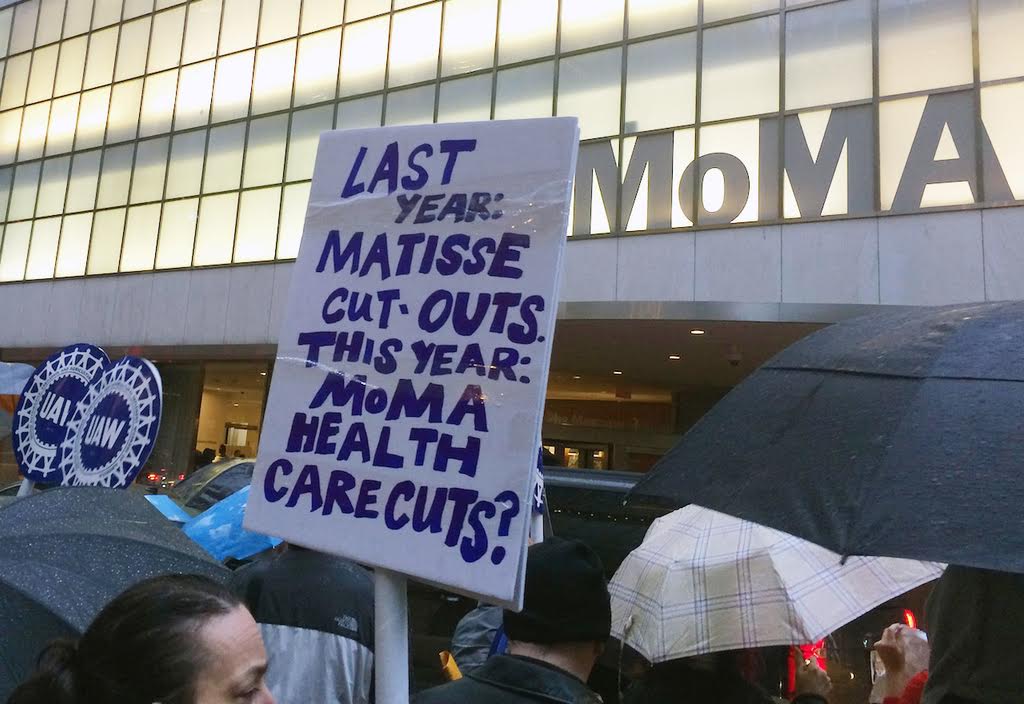

Down the line, there will almost certainly come a time for public-facing pressure campaigns. “Something that’s quite unique to cultural institutions is that funders are very sensitive to public perception,” Mahmood says. The reputational damage to the museum of having workers on strike in front of the main entrances is therefore likely to have real financial effects, and can be a significant source of leverage when the time comes to win a good first contract or negotiate a new one.

Back at MoMA, being organized for decades and periodically flexing the union’s muscle – including a 134-day strike of 250 workers in 2000 – has yielded pay and conditions well above industry standards. “Wages are higher at MoMA, especially for entry-level museum staff who would likely be really abused in other places. We’ve been able to protect benefits, and people have workplace rights that they wouldn’t have in another place,” Rosenstein says. “All of that should sound very familiar,” she adds. “They’re the same kinds of issues that a factory worker would be organizing around too.”